A blonde girl wearing a red poppies wreath, Ukrainian costume, necklace, and holding the bandura in her hands — that is how 17-year-old Maria Vdovychenko looked at pre-war photos.

Until recently, she lived with her family in Mariupol, was the president of the school, studied bandura, and visited church with her parents.

Her life abruptly changed on February 24. Shelling of the city turned the house, which once was a shelter, into a ruin.

Recently, Maria’s family managed to get out of Mariupol. Along the way, they survived the occupation and filtration camp.

Maria shared with hromadske the story of her family. In the text below, we are citing her direct speech.

“The war started. We are leaving!”

On February 24, at 3:50 a.m., my mother heard the first explosion, rushed into my and my sister’s room, and said the scariest words: “The war started. We are leaving!”. Where are we leaving? How does it possible? We quickly stuffed our bags with warm clothes and food that was left.

We thought we could leave. But we failed — the city was closed.

Then the real horror began. People were running out of houses, trying to buy everything, withdraw cash, refuel cars under the sound of explosions in the background.

At noon our house was already shaking.

Which basement should we run in?

I called the head of the homeowner association and asked where to hide. He said, “our basement is not designed for this, there are windows, and it is under renovation, you can’t go in there.”

At that time, we still had access to all utilities.

We had relatively small stocks of food and water because we thought we should get through only 3-4 days.

“You can’t last long in a bath an ordinary Khrushchyovka”

Two days have passed since the start of the war: phone connection, water, and light have disappeared. Later, the gas was cut off. We realized that the situation was complicated.

Mariupol was under shelling all this time. The city’s left bank was destroyed, explosive waves reached Primorsky District, and everything was trembling.

We darkened the windows in our apartment and put foam rubber between them. We thought it would protect us.

We decided to shelter in the bathroom. Sometimes, we knew what time we would be shelled. We immediately ran to the bathroom once we heard some noise, rustle, or explosion. Slowly, we got tired of it. There was no hope that everything would end, that we would be saved. “In the end, you can’t last long in a bath in an ordinary Khrushchyovka»

I don’t remember the exact date, but one morning, we were all lying in the same room and heard everything shaking in the apartment, something falling in the next room.

But we were lying and thinking that it was happening far away. We didn’t believe it.

The earth started vibrating, and our building seemed to bounce. We quickly locked ourselves in the bathroom. At first, we heard silence, it seemed like something was falling, and then the blast took everything down — the upper floors of the building folded like a house of cards. Fragments of concrete, furniture, roof, and glass were falling. People were screaming everywhere.

“People were ready to kill each other for a sip of water”

We managed to get out of the building. My father ordered us to head as soon as possible to the first basement we came across.

With ice, glass, noise, and gunfire all around us, we were running and hoping there would be a staircase to the basement and that a concrete slab would not crush us.

My sister reached the basement first, then did my parents and me. We knocked and heard that there were people inside — they were whispering. Finally, a man opened the door and said he couldn’t let us in because there were already many people in the basement, and there was no extra space. My father didn’t listen, he pushed him away, and we went in.

There were 20 people inside, our neighbors. Another family with a five-month-old child came in together with us. Few families would have died under our house if we hadn’t broken in.

We saw different horrors in the basement. People were running out of food, and it turned them into beasts. They were ready to kill each other for a sip of water.

There was no food to cook, we extracted water from ice and snow.

People run a great risk when going outside — fragments of buildings and stones were falling on them.

One day, a mine fell near our basement door. The hole was so big that it looked like someone had dug deep. We thought we would be buried under the rubbles because the building had already started collapsing. We were afraid that this would become our mass grave.

“Only our hope and prayer were in this basement”

My mother has been suffering from polyneuropathy for six years. It’s nervous system impairment. Due to stress, she stopped walking, her heart stopped twice. Pharmacies didn’t work, and we didn’t have any medicines. The emergency department across our basement was destroyed.

My father resuscitated my mother as best he could and knew; he gave her artificial respiration and heart massage. We were looking for medications under fire. We couldn’t lose mom. Only our hope and prayer were in this basement. That’s all.

On the 10th day in the basement, we had one piece of bread left. It was the size of my fist. We split it into four parts. I couldn’t eat my portion because we had been starving for a long time. I kept it for a very long time. I was afraid it would end, and I won’t have anything.

People quarreled among themselves and tried to kick someone out of the basement so that there was one less mouth to feed. There was no kindness, only darkness, we could feel the smell of death.

It lasted for 12 days.

“We won’t get out of here. It is my grave”

Usually, the shelling started around 4 in the morning. Then there was a short break, and it started again at 10 a.m. But on that day, everyone woke up at 2 in the morning to a noise no one had ever heard before. We were lying and tried to sleep. The сup on the shelf above me was bouncing. It sounded like four trains were passing by on each side of me.

Usually, during the shootings, a child was crying, and someone was reading a prayer aloud. But that time, everyone was silent.

Suddenly, the ground started to shake as if everything was flying at us. Plaster and bricks were falling from the ceiling.

I was lying there thinking: we won’t get out of here. It is my grave. I had already given up hope for everything. I could neither pray nor hope. It’ll be over, it can’t last for long. I was repeating to myself that human being suffers for something.

At that moment, I was sure that I would die, and I would not die alone. My family was lying on the same blanket with me.

I decided to pray. I asked God to die quickly without witnessing the deaths of my relatives and my helplessness towards their suffering.

We had nothing. No strength, no hope, not even a regular first-aid kit. Everyone knew that we wouldn’t get out of here if the basement was hit. Just like it happened in the building next to ours, where people hadn’t been pulled out of the rubble. Enemy soldiers didn’t allow to do this, so it was simply impossible.

“Either we starve to death, or we will be buried under the rubble, or just killed”

Since then, I don’t remember the days passing by. We were exhausted, hungry, and tired. My father once said: “Either we starve to death, or we will be buried under the rubble, or just killed.” The soldiers checked who was sitting in the basements and threw bombs. When someone knocked on our door, we didn’t answer.

One day our neighbors told us that we could go to Melekyne (Donetsk Oblast). Dad had an old Zhiguli car, damaged by buildings fragments and glass. We didn’t even know if the car would start, but it moved. We were driving under shelling and attacks from Grads. The battle continued, but we had only one goal: to survive, to get out of this hell.

We almost reached Melekyne — there was a “DPR” checkpoint. We realized that we couldn’t go back, but we didn’t want to go further: if they didn’t kill us there, they would kill us here; for the enemy, we are nothing but targets.

They stopped us at a checkpoint and asked our place of registration. “Mariupol? Go to the right.”

We didn’t know what does “right” mean. From there, they guided us further and further. Gradually a large column of cars and people who were walking was formed.

Then, the “DPR” military told to go “down.” We started moving, and they just started shooting at cars and people.

“With all our money, we could buy two loaves of bread”

We got to Yalta (Donetsk Oblast, Ed.), where we were hiding for more than 10 days in an old boarding house. We had no food and took water from the well. The cash we had left was nothing.

In Yalta, they were establishing “DPR,” and they allegedly tried to show themselves on the good side. They invited us to come to them and tell our first and last names to receive humanitarian aid. People went there to survive, not to starve to death. But there was no food: locals took everything sold in the market at huge prices.

In Yalta, there were also several stores with products imported from Russia. Prices were high, and the queues were huge. With all our money, we could buy two loaves of bread. We were hiding the bread, so it wouldn’t be taken away.

At that time, the “denationalization” process continued in Yalta: soldiers were looking for as they “nationalists” and “fascists” in homes around the city. People were taken out in unknown directions, someone was killed.

Hunger, cold, and fear of freezing

In Yalta, hunger, cold, and fear of freezing came to us again. All we had was fire, water, tea, and those two loaves of bread. My parents decided to leave.

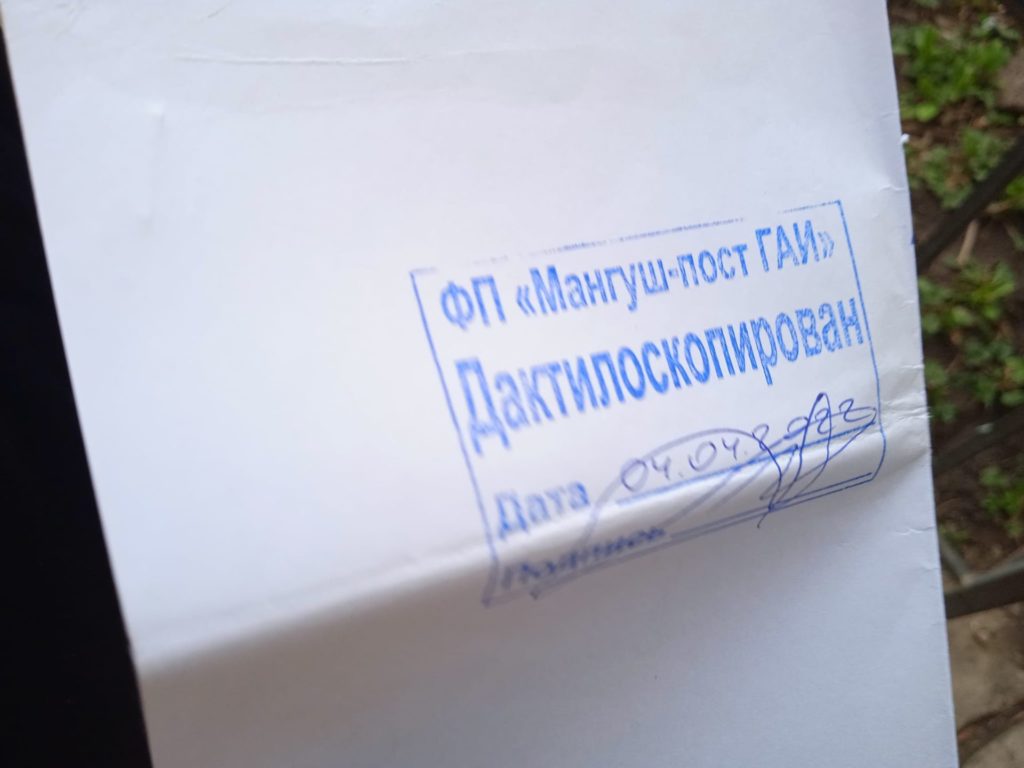

That’s how we got to the filtration camp in Mangush (Donetsk Oblast). There were two camps. The first one was for people who were walking. They could go through the filtration process for more than a month, and the queues were crazy. People tried their best to escape and run away. Another camp for designated for people with cars.

By camp, I do not mean some settlement, it was just columns of cars. There were 500 cars waiting in line in front of us and thousands more behind us.

It was forbidden to get out of vehicles, look for food and water, or go to the toilet. Everywhere armed soldiers were threatening people, checking that everyone was in place.

This filtration camp, as we were told, worked from 5 a.m. to 11 p.m., but in reality, nothing started until they woke up, had breakfast, smoked, talked on the phone, and rotate.

They didn’t care about civilians. In one hour, they checked two, at most, three cars. We lived in the car for two days while waiting for our turn.

“Filtration starts at the age of 14”

Here’s how filtering works: they have a checkpoint where a car drives in, there they check every pocket, glove compartment, trunk, every bag. They checked people’s clothes and what was underneath. They undress men outside near cars looking for tattoos, some marks on the bodies looking for “nationalists.”

Sometimes, only part of the passengers was undergoing filtration: soldiers could take only the father or mother, and the car had to move on. People were disoriented. Soldiers had weapons, but the people had nothing.

Our turn came at 11 p.m., we were the last car on that day. They let us in and searched us. My mother couldn’t walk anymore because of her illness. They allowed my mother and my younger sister to stay in the car, saying that “filtration starts at the age of 14”.

My father and I went out. At a distance of 200 meters from our car, there was a booth with two rooms. Exhausted people were standing on the street, they had no warm clothes, it was freezing outside. My feet were so frostbitten that I couldn’t feel my toes.

They just walked around, talked to each other, and discussed tortured women.

I heard their conversations:

“And the one who didn’t pass, where did you put him?” one soldier asked the other.

“I shot him. 10 people, maybe more. I don’t count. I’m tired of it.”

One man who passed the filtration came out, his eyes were huge and full of fear. He was shaking. He said that he had been through a brutal interrogation, he was beaten. His woman was never released.

“They tried to find people who love their homeland, who wanted to live a normal life”

Later it was our turn. I went to one filtration room, my father to another.

They took my fingerprints, scanned my documents, and checked my phone. They asked provocative questions about the government, Ukraine, and my attitude. They tried to find people who love their homeland, who wanted to live a normal life. They bullied, humiliated, insulted, beat.

They took my passport and saw that I was 17. They didn’t like me, I looked too young, and they were looking for some young girls.

I was pushed out. I was escorted to the car by an armed soldier.

He pushed me because I was walking slowly. I fell and hurt my knee, but I realized if I didn’t get up and run to the car now, I wouldn’t come back. I ran as fast as I could.

My mother saw me alone. She started to panic: what about our father? He didn’t pass? Has he been killed? Is he being tortured? And I couldn’t say anything. I sat there and didn’t know what would happen next.

However, my father returned in 40 minutes. We saw him being pushed out. He went out and fell. Then, tried to get up and fell again. Yet he got to the car.

“After he was beaten in the filtration camp, my father lost his eyesight”

My father hit the gas, and we drove. There was no straight road to Berdiansk: the bridge was blown up, so we drove through the outskirts and villages. We saw corpses and destroyed military equipment.

Already on the way, my father started to have vision problems — he could not see.

In Berdiansk, we spent the night in a car. There, my father told me about his filtration.

He has also been ordered to show his documents, they took his fingerprints, undressed, and searched him. They started interrogation putting moral pressure on him. First, they pushed him. When they saw that his phone was empty, they asked, “Why is the phone empty? What are you hiding? We don’t believe you!”. So he just got hit on the head. He doesn’t remember who and how did it. He only remembers the moment when he walked out on the street. My father lost eyesight after he was beaten, but we still had to drive further.

From Berdiansk to Zaporizhzhia, there were 27 checkpoints — at each one documents and a car were inspected, we were asked if we were in filtration camps. They took away food and warm clothes from people, searched for cigarettes and even drugs and alcohol.

We were driving as the battle continued alongside. Something flew under the car and exploded, the car jumped up. My father told me not to worry — it might have been a firecracker. But we realized there are no firecrackers in war.

The road was difficult. We saw destroyed buildings, anti-tank mines in the middle of the road, tanks with Z letter in the yards, burned bodies along the road, broken cars. The forest burned all around us.

“Don’t be afraid. It is Ukraine”

At dawn, we reached Orikhiv in Zaporizhia Oblast. Stone blocks, сzech hedgehog, metal thorns were ahead of us on the road. It felt like it was getting easier to breathe, and then we saw the Ukrainian flag ahead.

At first, we were afraid it was a provocation. Is this another exam we must pass?

We were stopped. They said: “Good afternoon! Please show your documents.”

We showed it, although we were still convinced this was a provocation.

We were told: “Don’t be afraid. It is Ukraine”.

We started crying. We couldn’t believe that we were protected and had found our land.

Then we went to the center for refugees in Zaporizhzhia. My mother received medical assistance because she still couldn’t walk. My father was very ill: he couldn’t see. My sister and I were emotionally exhausted. We were psychologically broken.

Volunteers helped us get to Dnipro.

Two doctors examined my father in the city and concluded that he had an injury due to a concussion. One eye completely lost vision, and the other sees as if through a cellophane bag.

Volunteers sent us to Lviv so we could get high-quality medical care. There my father was examined again. Doctors told us that his treatment would be long, complex, and expensive, and he might have to go abroad.

“We can’t lose our father. He saved us, now we have to help him,” says Maria’s mother, Natalia Serhiivna, at the end of our conversation.

If you want to support Maria’s family — here she explains how you can do it.

The article was created with the support of the NGO Women in the Media and the Ukrainian Women’s Fund. Contents are solely the responsibility of the author. The information presented does not always coincide with the views of the UWF.

Source: Hromadske