Apparent War Crimes in Kyiv, Chernihiv Regions

(Kyiv) – Russian forces controlling much of the Kyiv and Chernihiv regions in northeastern Ukraine from late February through March 2022 subjected civilians to summary executions, torture, and other grave abuses that are apparent war crimes, Human Rights Watch said today.

In 17 villages and small towns in Kyiv and Chernihiv regions visited in April, Human Rights Watch investigated 22 apparent summary executions, 9 other unlawful killings, 6 possible enforced disappearances, and 7 cases of torture. Twenty-one civilians described unlawful confinement in inhuman and degrading conditions.

“The numerous atrocities by Russian forces occupying parts of northeastern Ukraine early in the war are abhorrent, unlawful, and cruel,” said Giorgi Gogia, associate Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “These abuses against civilians are evident war crimes that should be promptly and impartially investigated and appropriately prosecuted.”

Human Right Watch interviewed 65 people between April 10 and May 10, including former detainees, torture survivors, families of victims, and other witnesses. Human Rights Watch also examined physical evidence at the locations where some of the alleged abuses took place as well as photos and videos shared by victims and witnesses.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, Russian forces have been implicated in numerous violations of the laws of war that may amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity. Human Rights Watch previously documented 10 summary executions in the town of Bucha and several other northeastern towns and villages during Russian forces’ occupation in March.

In 1 of the 22 newly documented killings, in the Kyiv region, Anastasia Andriivna said that she was at home on March 19 when soldiers detained her son, Ihor Savran, 45, after they found his old military coat. On March 31, the day after Russian forces withdrew, Anastasia Andriivna found her son’s body in a barn about 100 meters from her house after recognizing his sneakers sticking out the barn door.

Civilians described being held by Russian forces for days or weeks in dirty and suffocating conditions at sites such as a schoolhouse basement, a room in a window manufacturing plant, and a pit in a boiler room, with little or no food, inadequate water, and without access to toilets. In Yahidne, Russian forces held over 350 villagers, including at least 70 children, 5 of them infants, in a schoolhouse basement for 28 days, severely limiting their ability to leave even briefly. There was little air or room to lie down, and people had to use buckets for toilets.

“After a week everyone was coughing violently,” said someone formerly held at the school. “Almost all the children had high fevers, spasms from coughing, and would throw up.” Another said some people developed bedsores from constant sitting. Ten older people died.

In Dymer, Russian forces held several dozen people, the men blindfolded and handcuffed with zip-ties, for several weeks in a 40 square-meter room in the town’s window manufacturing plant, with little food and water, and buckets for toilets.

Human Rights Watch documented seven cases of torture in which Russian soldiers beat detainees, used electric shocks, or carried out mock executions to coerce them to provide information. “They put a rifle to my head, loaded it and I heard three shots,” said one man who had been blindfolded. “I could hear the bullet casings falling on the ground, too, and thought that was it for me.”

Human Rights Watch documented nine cases in which Russian forces fired on and killed civilians without an evident military justification. On the afternoon of March 14, for example, as a Russian convoy passed through Mokhnatyn village, northwest of Chernihiv, soldiers shot to death 17-year-old twin brothers and their 18-year-old friend.

All of the witnesses interviewed said they were civilians who had not participated in hostilities, except for two torture victims who said they were members of a local territorial defense unit.

All parties to the armed conflict in Ukraine are obligated to abide by international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, including the Geneva Conventions of 1949, the First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions, and customary international law. Belligerent armed forces that have effective control of an area are subject to the international law of occupation found in the Hague Regulations of 1907 and the Geneva Conventions. International human rights law, notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights, is applicable at all times.

The laws of war prohibit attacks on civilians, summary executions, torture, enforced disappearances, unlawful confinement, and inhumane treatment of detainees. Pillage and looting of property are also prohibited. The internment or assigned residence of civilians is permitted exceptionally for “imperative reasons of security.” A party to the conflict occupying territory is generally responsible for ensuring that food, water, and medical care are available to the population under its control, and to facilitate assistance by relief agencies.

Anyone who orders or commits serious violations of the laws of war with criminal intent, or aids and abets violations, is responsible for war crimes. Commanders of forces who knew or had reason to know about such crimes but did not attempt to stop them or punish those responsible are criminally liable for war crimes as a matter of command responsibility.

Russia and Ukraine have obligations under the Geneva Conventions to investigate alleged war crimes committed by their forces or on their territory and appropriately prosecute those responsible. Victims of abuses and their families should receive prompt and adequate redress.

As a general matter, Ukrainian authorities should take steps to preserve evidence that could be critical for future war crimes prosecutions, including by cordoning off gravesites until professional exhumations are conducted, taking photos of bodies and the surrounding area before burial, recording causes of death as possible, recording names of victims and identifying witnesses, and looking for identifying material that Russian forces may have left behind.

“It’s increasingly clear that Ukrainian civilians in areas occupied by Russian forces have endured terrible ordeals,” Gogia said. “Justice may not come quickly, but all steps should be taken to ensure that those who suffered see justice someday soon.”

For more information on the abuses documented in the Chernihiv and Kyiv regions, please see below.

Summary Executions

Human Rights Watch has documented 32 apparent summary executions by Russian forces in Kyiv and Chernihiv regions, including 10 in a previous report on Bucha. Summary executions, irrespective of the victim’s status as a civilian, prisoner of war, or otherwise as a captured combatant, are serious violations of the laws of war. Anyone who orders or commits summary executions is responsible for war crimes.

Kyiv Region

Andriivka

Anastasia Andriivna, 66, the mother of 45-year-old Ihor Savran, lives in the village of Andriivka, 40 kilometers northwest of Kyiv. She said that when Russian forces took control of the area on February 26, they came to her home, confiscated her and her son’s cellphones, and threatened to kill anyone who kept a working phone. She gave them an old phone and hid her newer, working phone. On March 19, a commander and a soldier came to her door, demanding that she let them inside. They said they had a device that had sensed cell phone usage coming from the area. The commander took her into one room to search for the phone, while the soldier dragged Savran to a summer kitchen in the yard. Anastasia Andriivna heard the soldier find Savran’s old military overcoat, from his 1993 National Guard service, and start shooting at it. The commander ordered her to stay in the house for the next 30 minutes, “without moving,” and left with the soldier, taking Savran.

On the night of March 30, Russian forces withdrew. The next morning, Anastasia Andriivna left home for the first time in weeks, hoping to find her son. About 100 meters from her home, she recognized her son’s sneakers, with a red stripe, sticking out of a barn door. She said:

He was lying there in a fetal position, with his hands tucked under his head, and his jacket draped over his shoulders. He had been shot in the ear, with blood covering his face. His best friend [Volodymyr Pozharnikov] was lying next to him; he had also been shot. His legs were bent in an unnatural position.

The stepfather of Anton Ischenko, 23, said that Russian forces came to their home in Andriivka and took Ischenko on March 3. Anton had been in the Ukrainian armed forces years earlier. The family found his body in a field in the suburbs of the village on March 31, the morning after Russian forces left the area. The stepfather declined to detail the state of Anton’s body but said that they had to identify him by his clothes.

Motyzhyn

On April 4, a Human Rights Watch researcher in Motyzhyn, a village about 50 kilometers west of Kyiv, saw the body of a woman whom the authorities identified as the mayor, Olha Sukhenko, 51, along with the bodies of her husband, Ihor, and son, Oleksandr. There was a fourth body, an unidentified man, who had tape covering his eyes and zip-ties lying next to him, indicating he may have been bound. His head had a large hole in it.

The four people appear to have been summarily executed, but Human Rights Watch was not able to confirm the circumstances of their deaths. A fifth body, an unidentified male with bruises and other marks, was found in a well nearby the mass grave on the same property. Human Rights Watch found evidence on the property and in the area in which the bodies were found that suggested that Russian troops occupied the area for an extended period, including discarded and partially consumed food and clothing consistent with that worn by Russian forces.

Chernihiv Region

Novyi Bykiv

A Novyi Bykiv villager whom Russian forces had held with about 20 others in a boiler room said that on March 30, a day before the Russian forces withdrew, several soldiers came to the boiler room saying that they had an order to execute 8 detainees and asked if there were any “volunteers.” When no one stepped forward, they took away eight men. The following day, after Russian forces withdrew, the villager found the bodies of two of the eight men about 50 meters from the boiler room, their heads smashed. He said he heard that the body of a third detainee was also found a bit further away. Human Rights Watch has no information about what happened to the other five men.

Staryi Bykiv

Russian forces in the village of Staryi Bykiv rounded up at least six men on February 27. Viktoria Hladka, the mother of one of the men, said she was sheltering in the family basement when Russian forces took her son Bohdan, 29, and brother-in-law Oleksandr Mohyrchuk, 39, from their yard. They had been smoking cigarettes, having just come up from the basement. Bohdan was a post office employee while studying management in Kyiv, and Mohyrchuk was a construction worker. Hladka saw their dead bodies and four others in a field the day after the men were taken.

Human Rights Watch documented these killings through a telephone interview with Hladka just after Russian forces withdrew from the village. Human Rights Watch on April 16 went to Staryi Bykiv and spoke with Hladka, who said that following the Russian forces’ departure, Ukrainian law enforcement officers exhumed the bodies. An examination showed that some of her son’s ribs had been broken, and he had a knife wound to the heart and a shot in the head. Mohyrchuk had a knife wound near the heart and his neck had been slit. Hladka also provided the names of the other men found dead: Oleksandr Vasylenko, 39; Volodymyr Putiata, 46; Ihor Yavon, 32; and Oleh Yavon, 33.

Yahidne

In Yahidne, Russian forces held over 350 villagers in a schoolhouse basement for 28 days, severely limiting their ability to leave, even for brief periods. Valerii Polrui, a local councilman from Yahidne, said that a village resident, Viktor Shevchenko, was shot on March 3, the day Russian forces arrived in the village. Polrui said that one of the soldiers told him that Shevchenko was shot because he was a major in the Ukrainian armed forces, which he said was untrue. Shevchenko’s body was found a month later, buried in his own backyard. Ukrainian law enforcement officers exhumed Shevchenko’s body and conducted a forensic exam. Polrui said that the forensic exam showed that Shevchenko was shot in the head.

The bodies of two men who had been visiting Yahidne were found in a cellar on March 6 or 7. A villager who saw the bodies said their hands were tied behind their back and that each had two bullet wounds, in the head and in the back. Both were in their 40s.

Petro Tolochyn, in his 50s, was believed to be a retired lieutenant colonel who had a holiday home in Zolotynka, about 6 kilometers from Yahidne. One of the women held in the school basement and who sat close to the door, which had cracks in it, described seeing an armored vehicle bringing Tolochyn, covered in a blanket, to the schoolyard. She saw Russian soldiers put him on his knees and question him, and then throw him into the boiler room on the other side of the schoolyard.

The following day, the soldiers brought him to the basement, but took him away next morning, allegedly to take him to a hospital. Another villager in the basement who said he knew Tolochyn well and recognized him there, said Tolochyn’s body was discovered after Russian forces withdrew on March 31. Human Rights Watch visited the school on April 17 and saw a body bag. A villager who had identified Tolochyn’s body said it had gunshot wounds to the temple and left leg.

Mykhailo-Kotsiubynske

On March 4, Russian forces detained Oleh Prokhorenko, 38, in the town of Mykhailo-Kotsiubynske. He was allegedly using his phone to film Russian troop movements and provide the information to Ukrainian forces. Witnesses said they saw Prokhorenko, after he was detained, digging trenches for the Russian soldiers, a laws-of-war violation. Then no one saw him for weeks. His body was found on April 8 in the nearby woods, shot and buried. The forensic exam on file with Human Rights Watch says that he had gunshot wound to the head with skull fracturing and brain destruction.

Unlawful Killings of Civilians

Human Rights Watch documented nine cases of apparently unlawful killings of civilians by Russian forces in the Chernihiv region. Parties to an armed conflict, including occupying forces, may not attack civilians unless they are directly participating in the hostilities. Parties must do everything feasible to verify that targets are military objectives, such as soldiers, weapons, and military equipment.

On March 14, between 1 p.m. and 2 p.m., as a Russian convoy passed through Mokhnatyn village, soldiers shot to death 17-year-old twin brothers Yevhen and Bohdan Samodiy and their friend, Valentin Yakimchuk, 18. Yevhen and Bogdan were in vocational training to become electricians, while Yakimchuk was a first-year university student in Chernihiv.

The twins’ sister, Tanya, and other witnesses said that Russian forces had not occupied Mokhnatyn. Tanya said by phone that a Russian convoy earlier that day had been attacked near Mokhnatyn, and vehicles had scattered to various villages, including Mokhnatyn.

Tanya, who lived on the main road, said that her brothers and Yakimchuk had left for a friend’s house early that afternoon. She was at home when she heard the rumble of a convoy heading from the village center on the main road toward her house. After shots were fired, she immediately ran toward the village center and saw about 10 Russian military vehicles on the road, including armored personnel carriers, vehicles hauling rockets, and a gasoline supply truck.

When she arrived at the site of the incident, neighbors told her to get her parents. When she returned with them, they saw the bodies of the three on the ground. Yevhen and Yakimchuk were dead. Witnesses said half of Yakimchuk’s head was gone and Yevhen had been shot in the chest. Bohdan was wounded in the abdomen and still alive. His mother and her partner drove him to the Chernihiv children’s hospital, but Bohdan died before they arrived.

On March 4, in Nova Basan village, Russian soldiers shot dead Dmytro Solovei, 14, who was kicking around a football on a playground near his house. His brother, Serhii, 30, who saw Dmytro playing, went outside to bring him in, but also got shot at and wounded in the leg. Serhii managed to crawl to a neighbor’s house and get first aid. He could not seek professional medical assistance until Ukrainian forces regained control of the area on March 31. Their mother, Anzhela Solovei, said on May 10 that Serhii remained hospitalized, and his recovery was expected to take several months.

On February 28, also in Nova Basan, Russian soldiers apparently shot Mykola Kucherina, about 40, in the head as he passed by their post. The village administration chief said that although the family knew about Kucherina’s death, his body remained there for a month, as the Russian forces did not allow his parents to collect it.

Three residents of Levkovychi village said that around 6 p.m. on February 28, Russian forces entered the village and shot dead four men – Oleksandr Oryshko, Oleksandr Derkach, Yaroslav Varava, and Serhii Nimchenko – in the village center. The residents said that the men were unarmed and that each suffered multiple bullet wounds.

Enforced Disappearances

Human Rights Watch documented six cases in which Russian forces detained civilians, but their families could find no information about their circumstances or whereabouts. During an international armed conflict, failure to acknowledge a civilian’s detention or to disclose their whereabouts in custody can constitute an enforced disappearance, a crime under international law. The United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine has since February 24 documented 204 cases of enforced disappearances involving 169 men, 34 women, and a boy, the overwhelming majority of them attributed to Russian armed forces and affiliated armed groups.

Russian soldiers detained Anatolii Shevchenko, a Yahidne resident in his 40s, on March 4. His next-door neighbor saw him being apprehended and again later sitting handcuffed on the concrete near the schoolhouse where other residents were arriving to shelter in the school basement. For a month, Russian forces used the school as their base. Shevchenko’s family members told the neighbor, who sees them regularly, that they had received no news of Shevchenko’s whereabouts.

On March 4, around 3 p.m., five Russian soldiers detained Mykyta Buzinov, a 24-year-old taxi driver in Chernihiv city, at his house in the town of Mykhailo-Kotsiubynske. His uncle, Borys Buzinov, who was at home at the time, said that the soldiers checked everyone’s phones and saw that Nykyta had provided information to the Ukrainian forces. The soldiers first took Buzinov and his girlfriend, Katya, and then his mother and uncle to a nearby veterinary clinic, where the Russian forces were encamped.

Later that evening, the soldiers released everyone except Buzinov, saying they would talk to him and release him later. The encampment relocated the following day and Buzinov has not been seen since then. Borys Buzinov has been trying to locate Nykyta since his detention and spoke to members of various Russian units stationed throughout Mykhailo-Kotsiubynske in March, but he could not obtain any information about his nephew’s whereabouts.

Natalia Tarashenko, 48, and her husband, Mykola Sadovyi, 47, residents of Krasne, Chernihiv region, moved to her mother’s house on the other side of the town because their house was close to Ukrainian positions on the main road. Her husband stayed to take care of the household and domestic animals. On March 9, their neighbor’s child came to Natalia to say that her husband had not been seen for two days.

Sadovyi had told the neighbor on March 7 that he had run out of his heart medication and was planning to bicycle to Chernihiv to buy it. He was with his friend, Kostya Sivko, who also disappeared the same day. They are concerned that Russian forces took them into custody. Although Krasne remained under Ukrainian control, to get to Chernihiv, the men would have had to ride on roads controlled by Russian forces, through Russian checkpoints, and also pass through Yahidne, which was under Russian control at the time.

On March 10, Serhii Molosh, 39, and his friend, Vitalii Kulik, were missing from the village of Ryzhyky, about 22 kilometers north of Chernihiv, and there are concerns that they were taken into custody. Serhii’s mother, 69, said the men set off by foot during daylight hours to buy meat in the village of Riabtsi, 2.5 kilometers away. They never reached Riabtsi and were not heard from since. Villagers knew of no shelling in either village or on the road between them. Russian forces were in full control of the area where Ryzhyky and Riabtsi are located, and Russian armored vehicles were patrolling the road between both villages as well as other neighboring villages.

Unlawful Confinement and Inhuman, Degrading Detention Conditions

Human Rights Watch documented numerous cases in which Russian forces rounded up and unlawfully detained civilians in dirty and suffocating conditions, restricting their access to food, water, and toilets. The Fourth Geneva Convention applies to all civilians, who are considered protected persons when under the control of belligerent or occupying forces. The Geneva Conventions permit the internment or assigned residence of protected persons only for “imperative reasons of security,” as a measure of last resort. In the cases investigated, Human Rights Watch found no basis for detaining civilians. The ban on torture and other ill-treatment is absolute under both the laws of war and international human rights law.

Chernihiv Region

Yahidne

Russian forces entered Yahidne, a small village 15 kilometers south of Chernihiv city, early March, after days of shelling. For 28 days, they held over 350 civilians, almost the whole population, in the basement of the village schoolhouse without ventilation in extremely cramped and unsanitary conditions. They severely limited people’s ability to leave the basement, even for brief periods, arbitrarily depriving them of their liberty. Seventy were children, including five infants. During this time, 10 died, all older people.

On March 3, Russian forces rounded up the villagers or otherwise ordered them to the school basement ostensibly for their own safety. Some refused and were allowed to remain in their homes because they were sick or were providing someone health care.

Russian forces turned the school into a military base, thereby endangering the villagers detained there.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 13 people detained in the basement, which consisted of two large rooms and a warren of six smaller rooms. They said that during the first few days Russian soldiers did not open the door at all, and subsequently opened it no more than once a day, allowing people to leave irregularly to use the outdoor toilet and to cook over outdoor fires, and at times allowing some detainees to go home to bring food back to the basement. They described the suffocating lack of air, the absence of space to move around or lie down, and having to use buckets for toilets. Many fell ill.

Some villagers went voluntarily to the basement, fearing the continued shelling. Some were directly coerced. Olha Volodymyrivna said that on March 3, three Russian soldiers came to her house, beat and kicked her husband, Volodymyr, 63, in her presence, smashed his phone, and locked both in their stand-alone cellar for two days, while the soldiers lived in their house. On the third day, they ordered the couple to go to the school basement.

On March 3, Volodymyr Ivashchenko was sheltering in the basement of his home with his wife, mother-in-law, daughter, and 3-year-old grandson, when five soldiers banged on the basement door and ordered everyone out. Ivashchenko’s 70-year-old mother-in-law, who walked with a cane, remained inside. Ivashchenko explained to the soldiers that she had difficulties walking. She left the basement only after one of the soldiers threatened to drop the grenade he was holding if she did not leave. The following day, Ivashchenko and his family walked to the school basement. He described the conditions there:

It was damp and everyone was coughing. There was not enough air…. There were hundreds of people [and] nowhere to sleep, we were locked there for days at a time, used buckets as toilets. Imagine sitting on a chair for weeks, no place to even lie down.

A woman from Yahidne said:

The room had no light. We could only sit on small children’s chairs or narrow benches. Our baby was sitting and sleeping on laps. The air was filled with dust and the smell of lime from the walls. … After a week everyone was coughing violently. Almost all the children had high fevers, spasms from coughing, and would throw up. We tried not to walk unnecessarily, because people were sitting so densely that it was only possible to move sideways…

We tried not to drink much because there was not enough water, and we were anxious that the soldiers would not allow us to use the … small outdoor toilet. They … [soldiers] didn’t give us food during the first days. … After that, they allowed some of us to go home for food supplies. They allowed us to make a fire near the exit and cook for ourselves. We were able to provide a half liter of [cooked] food per two people.

She also said the soldiers would not allow a 63-year-old man with cancer, for whom sitting was painful, to go home. They said he could “hang himself” to alleviate the pain. Some people developed bedsores from constant sitting. Around March 20, several children and adults came down with chickenpox and secondary infections from scratching the blisters.

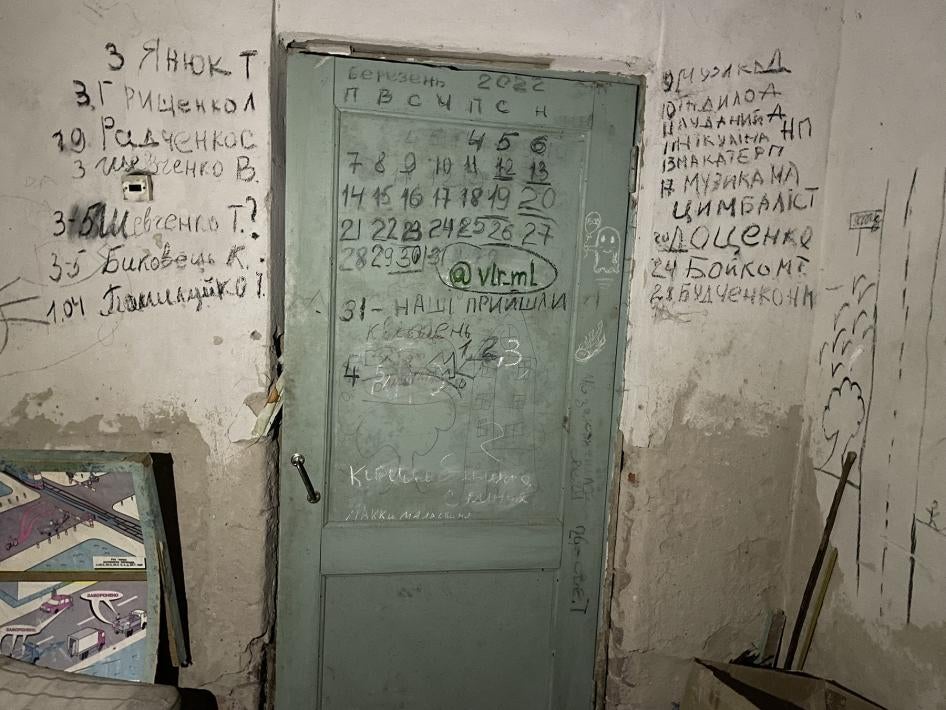

Halyna Tolochyna, who spent nearly a month in the Yahidne school basement, said that to keep track of days, together with another woman, she drew a calendar using chalk on one of the basement doors. On the right side of the door, she kept a list of people who died, 10 in all, including their date of death, and on the left, a list of people, totaling 7, who were shot or were forcibly disappeared.

Tolochyna said 2 of the 10 people had died at home a few days after the soldiers let them leave because of their rapidly deteriorating health. Among the eight who died in the basement was Ivashchenko’s mother-in-law, Nadiia Buchenko. Ivashchenko said:

Imagine sitting on a chair for weeks. Nowhere to lie down, and not enough air. Her legs got swollen and her blood pressure would drop a lot. We had no medications and could not leave. She died on March 28. Her body was moved to the boiler-room and two days later, Russian soldiers allowed me to … bury her at the cemetery.

Some former detainees were still hospitalized when Human Rights Watch visited on April 17 for various ailments they contracted during their confinement.

Among them was Ivashchenko’s wife, Liubov, 50, who went to the hospital on March 31, the day they were released. Her legs had become swollen, and she was having difficulty walking.

Nova Basan

Mykola Diachenko, 63, head of the village administration in Nova Basan, spent 26 days in Russian custody, in five locations, including a post office building, a warehouse, a summer kitchen, and a cellar.

Russian soldiers detained Diachenko on March 5 at home, together with his deputy. Diachenko said that the Russian soldiers rounded up every man on his street as the soldiers were establishing control over the village. He said:

They demanded that we put on some clothes and follow them. I asked if I could take my eyedrops, [they said] I would not need them anymore. I thought they knew I was the head of the village administration, and they were going to shoot me.

One of the detention places was in a stand-alone underground cellar, which was no more than nine square meters, with 20 detainees, all men from 22 to 65. They spent two days there, with the door sealed shut. People started to suffocate. Diachenko said, “We started banging on the door, pleading [for someone] to open it and let us breathe. Eventually, the soldiers left the door slightly open to let some air in.” The men inside were given no food, only two liters of water for the 20 to share.

Novyi Bykiv

On March 24, seven or eight Russian soldiers came to the home of Volodymyr Zhadan in Novyi Bykiv, started shooting in the air, and demanded that he hand over his phone. Zhadan, 64, said:

I was in my underwear. … They started to beat me [with rifle butts], pushed me to the ground and started to kick me in the stomach, legs, back, demanding my phone. …Then they blindfolded and handcuffed me from behind and took me away. They only allowed me to put on my slippers and a jacket, no pants.

Zhadan said he was taken, together with two neighbors, to the basement of the village preschool. “They took the blindfolds away, but it was completely dark,” he said. “We spent the night there, freezing in complete darkness.” In the morning, the Russian soldiers gave him pants, blindfolded him again, and took him for questioning next door at the village school. After Zhadan was released, later that evening, he found his house had been trashed and looted.

On March 24, soldiers detained a 66-year-old Novyi Bykiv villager because they found he had a cell phone. They took him to a small boiler room in the village center, which was holding about 20 people. In the far-right corner was a pit several meters deep. Soldiers put him in the pit, where he spent five nights together with four other detainees. He said he was allowed to use the toilet only three times during the five days, that they were given no food and just one bottle of lemonade a day for all five men. “One of the detainees was in handcuffs all the time; his hands were swollen,” the villager said.

Kyiv Region

Dymer

After the Russian offensive began on February 24, Ihor Zyrianov, a 58-year-old hair stylist from Kyiv, fled to his summer house in Bohdany, a village about 80 kilometers north, together with his wife and 12-year-old daughter. On the morning of March 21, Zyrianov and five friends, including two women, got together at the home of his neighbor, Pavlo Rudyk, 47, because he had internet reception. Soon six Russian soldiers, wearing masks, arrived in an armored vehicle. They ordered everyone out, checked their documents, and stole US$11,000 that Zyrianov said he had in his passport folder.

The soldiers confiscated the two vehicles parked in the yard, took off the license plates and sprayed a “V,” one of the Russian symbols for the Ukraine conflict, on them. They blindfolded the four men, handcuffed them behind their backs with plastic zip-ties, and bundled them in the trunks of the two cars. They put the two women in the back seat of one of the cars and drove all six about 30 minutes to the window manufacturing plant complex in the town of Dymer.

There, they were taken to a 40 square-meter room that Zyrianov described as a compressor station with a big industrial air pump in the middle of the room. The six friends spent three days in custody there. At least 30 others were already in the room when they arrived, and the number grew to 49 by the end of the day. Zyrianov said the detainees ranged in age from 17 to 73, and that at least eight were 17 and 18, and that one young man had been detained there for two weeks before they arrived.

Zyrianov and Rudyk, interviewed separately, each said there was very little light in the room. There were two buckets instead of toilets, one 20-liter bottle of water and one hose for drinking and that everyone, except the women, was kept blindfolded and handcuffed with zip-ties.

Zyrianov said:

The door had a small hole, which allowed enough light for us to know whether it was a day or night. People slept and sat on the ground, on plastic buckets, or on some cloths, no beds… There was not enough space for us to lie down, so we slept in shifts. Food was given once a day… Once there was barley, once pasta, and once some kind of boiled rice. We… learned how to loosen the zip-ties when the door was closed and would lift the blindfolds when Russian soldiers were not there.

On March 23, a Russian officer told the detainees that they would be released in groups. Zyrianov, Rudyk, and their four other friends were in the second group, together with three others. They were taken, blindfolded and handcuffed, to the center of Dymer at around 4 p.m. Zyrianov said that the Russian soldiers told them that they would be killed on the spot if they were detained again.

When they returned home, both men discovered that their houses had been looted. Rudyk said that among the items stolen were a car, his wife’s wedding ring, a generator, tools, Bluetooth speakers, about $30,000 in cash, and a watch worth US$22,000.

Torture and Other Ill-treatment

Dymer

Zyrianov and Rudyk described the abuses they endured during their three days of detention at the window manufacturing plant. Zyrianov said that on the first day, March 21, Russian soldiers confiscated their phones and demanded access codes. Each day, soldiers interrogated them, one by one, for 10 to 15 minutes each, in a nearby room. He said that the soldiers had nicknames for all detainees, and they called him “American” because of the US visas in his passport.

He was interrogated, while blindfolded, three times about where he served in the military and why he had traveled to the United States. Soldiers hit him twice with a rifle butt when they did not like his responses. Zyrianov said that he was spared compared to others: “They used ‘electric shockers’ and beat some detainees. We could hear the screams.”

Rudyk said soldiers interrogated him twice and subjected him to a mock execution:

I sat blindfolded and handcuffed. They told me that it was over for me. They put a rifle to my head, loaded it and I heard three shots. I could hear the bullet casings falling on the ground too. …They told me that they would not miss next time if I don’t tell them everything… whether I participated in the Maidan events [2013 protests in Kyiv] or whether I fought in the 2014 war. Second time they interrogated me, they used an electric shocker on me. They shocked me on the back of my head. It was very painful.

Rudyk said that as of mid-April, more than 40 people detained at the window manufacturing plant were still missing. Rudyk and Zyrianov said that on April 14, two other detainees – a Red Cross volunteer driver and a nurse – were missing after the ordeal. In an April 27 CNN report about the window manufacturing plant industrial site, reporters interviewed Volodymyr Khrapun, a former detainee whom Russian forces forcibly transferred to Russia, together with dozens of other window manufacturing plant detainees. Khrapun appears to be the Red Cross driver whom other detainees had described, and who told CNN he was released as part of a prisoner exchange.

Nova Basan

Mykola Diachenko, the Nova Basan village administration head, said that at one of the five sites where he was held, Russian soldiers took him outside with other detainees. They blindfolded them and demanded that they cooperate if they wanted to survive. Diachenko then heard rifle shots, thinking that someone had been executed. They also threatened to hang him by his feet, stab his fingers, and impale him on a wooden pole so he “would die in a lot of pain.” At the fifth detention site, a small summer kitchen packed with detainees, the soldiers threatened to throw in a grenade. “I was sure that I would not survive the detention,” Diachenko said. He and others detained with him were freed after Russian forces withdrew from the area.

In Nova Basan, Human Rights Watch spoke with a villager who participated in the local territorial defense unit, the quasi-military resistance groups in Ukraine against Russia’s invasion. On March 9, about 15 Russian soldiers arrived on an armored vehicle and took the villager and his 25-year-old son, also an active resistance member, at gunpoint. They pushed them to their knees, while firing their rifles in the air, tied their hands behind their back and ordered them to show where they had hidden their guns.

The soldiers took the son to their basement and made him dig out buried guns. The soldiers blindfolded the villager, put him in an armored vehicle and took him to a farmhouse. “They put me on a chair,” he said. “I told them that I had given them all the weapons I had, but someone then kicked me in the back of the head, and I fell off.”

The soldiers released him the next day, detained him again on March 12 and held him until March 31. They took him back to the farmhouse and threatened to cut his hands off or run over him with a tank if he did not tell them more about the resistance.

The villager said that one soldier tied his hands together in front with a zip-tie and hung a cable from the ceiling roof, pulling his hands upward, the tips of his toes touching the floor. He said the only way to avoid pain was to stand on tiptoes. He was kept in this position for two or three hours. He was set free after Russian forces withdrew from Nova Basan.

Hostomel, Kyiv region

Oleksandr Novichenko, 35, evacuated his mother from Hostomel, but stayed behind to feed his and his neighbors’ domestic animals. On the afternoon of March 27, as he was closing the neighbors’ gates, a Russian soldier took him into custody, tied his hands behind his back with a zip-tie, blindfolded him, and pushed him down into a basement, where for two days soldiers repeatedly questioned and electroshocked him.

“The zip-tie was so tight that my wrists were swollen,” he said. “I had an open wound on my knee, and they would shock me right there … I was screaming from pain, telling them that I knew nothing, but they would go on shocking me.” After two days, the soldiers put a black bag over his head and released him in the village.

Source: Human rights watch